The University of Lahore Students’ Research Article on Influenza Virus

(Publish from Houston Texas USA)

Authors:

⦁ Muhammad Zohaib Ashraf

⦁ Ayesha Mudassar

⦁ Fatima Mohsin

“Microscopic view of influenza virus particles. Health experts warn of rising flu activity this season.”

Abstract

Influenza A viruses (IAVs) possess a great zoonotic potential as they are able to infect different avian and mammalian hosts, from which they can be transmitted to humans. This is based on the ability of IAV to gradually change its genome by mutation or even reassemble its genome segments during co-infection of the host cell with different IAV strains, resulting in a high genetic diversity. Variants of circulating or newly emerging IAVs continue to trigger global health threats annually for both humans and animals. Here, we provide an introduction to IAVs, highlighting the mechanisms of viral evolution, the host spectrum, and the animal/human interface. Pathogenicity determinants of IAVs in mammals, with special emphasis on newly emerging IAVs with pandemic potential, are discussed. Finally, an overview is provided on various approaches for the prevention of human IAV infections.

Zoonotic influenza viruses are influenza strains that originate in animals—primarily birds, pigs, and other mammals—and cross the species barrier to infect humans. These viruses pose a significant public health threat due to their ability to mutate rapidly and reassort their genetic material, creating novel strains with pandemic potential. Transmission typically occurs through direct contact with infected animals, contaminated environments, or intermediate hosts.

Notable zoonotic influenza subtypes include H5N1, H7N9, H9N2, and H1N1, each associated with varying degrees of morbidity and mortality. The emergence of these viruses underscores the importance of continuous surveillance, early detection, and a One Health approach to prevent interspecies transmission.

Introduction

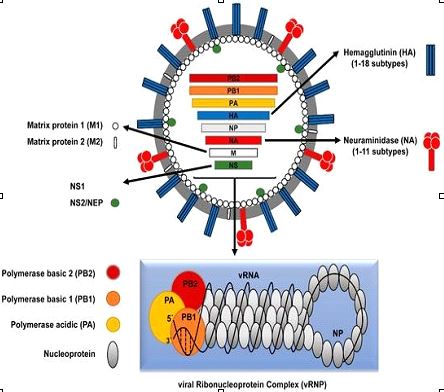

Influenza is a contagious respiratory disease caused by influenza viruses (IVs). IVs are categorized antigenically based on the variations of the nucleoprotein (NP) into four genera: influenza A viruses (IAV), influenza B viruses (IBV), influenza C viruses (ICV), and influenza D viruses (IDV). Together with Isavirus, Thogotovirus, and Quaranjavirus, they compose the family Orthomyxoviridae.

Both human IAV and IBV trigger seasonal global epidemics, while human infections with ICV are less frequent and generally cause mild illness without reported epidemics. IDV mostly infects cattle and is not yet known to infect humans. IVs have a segmented, negative-sense, single-stranded (-ss) viral RNA (vRNA) genome. Both IAV and IBV contain eight vRNA segments, while ICV and IDV contain only seven segments. The eight genomic segments of IAV encode at least 10 viral proteins (figure 1).

Etiology

Zoonotic influenza etiology involves animal-origin influenza A viruses (like H5N1, H9N2 from birds; H1N1, H3N2 from swine) crossing into humans, typically via direct contact with infected animals or contaminated environments, causing mild to severe illness, with potential for pandemics if they adapt to sustained human-to-human spread. These viruses constantly evolve, with migratory birds and intensive farming acting as reservoirs, creating opportunities for genetic reassortment and spillover events.

Key Factors in Zoonotic Influenza Etiology:

⦁ Viral Reservoirs: Aquatic birds are the natural, long-term hosts for influenza A viruses, but swine act as “mixing vessels” where avian, human, and swine viruses can exchange genetic material.

⦁ Genetic Evolution: Influenza viruses are highly mutable, constantly changing, which leads to new strains and increased pandemic potential.

Common Zoonotic Viruses:

⦁ Avian (Bird) Flu: A(H5N1), A(H9N2).

⦁ Swine (Pig) Flu: A(H1N1), A(H3N2).

Epidemiology

Zoonotic influenza epidemiology involves viruses jumping from animals (especially birds/swine) to humans, causing mild to severe illness, with risks heightened by live markets, farming, and mutations/ reassortments leading to pandemic potential (like H5N1, H7N9). Key factors include animal-human interfaces, changing virus strains (e.g., recent A(H5N5)), and the need for “One Health” surveillance integrating animal/human data to track spread and prevent pandemics, using tools like serology to find asymptomatic cases.

Transmission

⦁ Source: Primarily avian (birds) and swine influenza viruses, which constantly evolve through mutation and reassortment.

⦁ Animal Reservoirs: Wild birds are natural reservoirs, while pigs act as mixing vessels for avian and human viruses.

⦁ Human Exposure: Direct contact with infected animals, live poultry markets, farms, and contaminated environments are major risk factors.

Pathogenesis

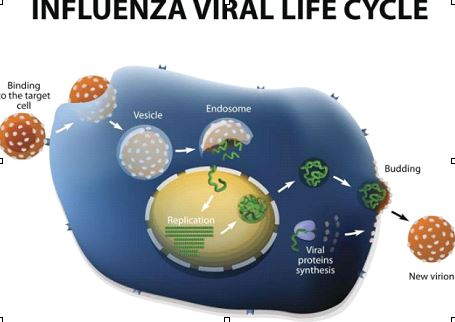

Zoonotic influenza pathogenesis starts with the virus (like avian H5N1, H7N9) binding to sialic acid receptors (a-2,3 linkages common in birds, a-2,6 in humans) on respiratory cells via its Hemagglutinin (HA) protein, entering via endocytosis, and replicating, causing cell death.

Initial Infection & Entry:

Viral Hemagglutinin (HA) binds to sialic acid receptors on host respiratory cells. Avian viruses prefer a-2,3 sialic acids (found deep in human lungs), while human strains prefer a-2,6 (upper respiratory tract). Zoonotic viruses need to adapt to bind a-2,6 for efficient human-to-human spread. The virus enters the cell.

Clinical Findings

Zoonotic influenza in humans causes flu-like symptoms (fever, cough, sore throat, body aches, fatigue, runny nose) but can rapidly progress to severe respiratory issues like pneumonia, Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS), respiratory failure, and multi-organ failure, often with gastrointestinal issues (diarrhea, nausea) or neurological signs (encephalopathy) as well as eye inflammation (conjunctivitis). The severity depends on the specific virus, but serious complications are common, ranging from mild illness to death.

Common Symptoms (Mild to Moderate):

Fever, Cough (often dry), Sore throat, Headache, Muscle/Body aches, Fatigue.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing zoonotic influenza involves clinical suspicion based on flu-like symptoms and animal exposure (birds, pigs, cows), using RT-PCR on respiratory samples (nasopharyngeal/throat swabs, bronchoalveolar lavage) for rapid detection, with conjunctival swabs crucial for H5N1 cases with eye symptoms, and advanced genetic sequencing for specific subtype identification, while serology helps track past exposure but not initial diagnosis.

Sample Collection:

⦁ Upper Respiratory

⦁ Lower Respiratory

Laboratory Testing:

⦁ Real-Time RT-PCR

Supportive Tests:

⦁ Serology (Blood tests for antibodies)

Treatment

Treatment for zoonotic influenza involves prompt antiviral drugs (like oseltamivir, baloxavir, zanamivir, peramivir) started early, plus supportive care (rest, fluids, fever reducers); severe cases need hospitalization and possibly combination antivirals or other supportive treatments, emphasizing early action after potential exposure to infected animals or symptoms appear.

Supportive Care:

⦁ Rest & Fluids

⦁ Pain/Fever Relief

⦁ Hospitalization

Prevention/Control

Preventing zoonotic influenza involves a “One Health” approach focusing on animal health (biosecurity, vaccination, surveillance), reducing human-animal contact (PPE, hygiene), enhanced surveillance in both, rapid diagnostics, global collaboration, and preparedness for human cases, with key actions like handwashing, avoiding touching face, using PPE, and biosecurity measures in farms/markets crucial for high-risk groups.

For Individuals (Especially High-Risk Groups like Farmers, Vets, Market Workers):

Hygiene, Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), Vaccination

For Animals:

Biosecurity, Animal Vaccination,

Surveillance

Conclusion

Zoonotic influenza viruses, primarily from birds and pigs, constantly threaten humans due to their ability to mutate, reassort genes (mixing with human viruses), and cause severe illness or pandemics, requiring urgent, global “One Health” strategies combining enhanced surveillance, biosecurity, rapid diagnostics, antiviral development, and public awareness to control animal-to-human transmission and prevent major outbreaks. A virus could gain the capacity for sustained human-to-human transmission, potentially causing a severe global outbreak. Human infections usually result from close contact with infected animals (e.g., poultry or swine) or contaminated environments, such as live bird markets or farms. Transmission pathways are complex and can be direct or indirect via contaminated water or surfaces. Prevention strategies focus on improving biosecurity and hygiene in animal farming and markets. Timely use of antiviral medications (like oseltamivir) for treatment and post-exposure prophylaxis.

Development of effective, broad-spectrum, or universal vaccines, though, is challenging due to viral diversity and rapid mutation rates.